Many commentators today are likening the Covid-19 pandemic to that of the Spanish flu which hit the world in 1917-1920. It was named as neutral Spain had no need to censor its newspapers and therefore the first reports of the ‘flu appeared in Spanish newspapers, particularly as the Spanish King Alfonso XIII was seriously ill with the disease. The first wave of the ‘flu was relatively mild in the summer of 1918, peaked heavily in October 1918 with a more virulent strain of the disease, and not fading out until April 1920. Eventually more died worldwide than all the civilian and military deaths of the first World War. Death rates were highest amongst the 20-40 year olds – the age of most of the soldiers returning to their homes after the war. There were no antibiotics or means of treating the illness.

At the time, the only means of information for the people of Cheltenham was through the local newspapers – principally the daily Gloucestershire Echo. News of the spread of the disease in areas where British soldiers were serving would have caused panic so information concerning places were troops were stationed was suppressed. There was a need at the end of the war to keep up people’s high morale on the Home Front to sustain “the last push” to victory. Therefore, information in newspapers, already heavily censored, didn’t necessarily reflect the full story.

Those at home reading the Gloucestershire Echo would have read of a number of tips to combat the ‘flu. One government official recommended regular teeth cleaning and the News of the World newspaper suggested readers should eat plenty of porridge! Cheltenham’s first female G.P. and Medical Superintendent at St. Martin’s Hospital – Dr. Grace Billings – firmly believed smoking cigarettes would keep the disease at bay and strongly advised her patients to do so.

A national newspaper reported that whilst hundreds of schools had closed in England, Cheltenham Boys’ School (the College) had taken the reverse step and locked staff and pupils inside the buildings. This was a huge disappointment to the local farmers who had applied to the college for pupils to help pulling mangolds and lifting potatoes. The college informed them none of the boys were available due to the epidemic.

One letter writer to The Echo suggested women ought to be employed to disinfect the streets as the disease was carried on dust and a Major from Tewkesbury suggested dandelion tea should be taken if quinine was not available, bonfires should be lit close to homes and returning soldiers’ clothes should be fumigated. He was sure, like the plague, that the disease was carried by insects. Another correspondent suggested those attending dances should wear masks fashioned like “oriental yashmaks”. A member of Tetbury Workhouse Guardians believed some inmates had died because they had not been able to obtain alcohol. Government advice was that face masks were considered ineffectual but goggles were recommended as it was thought the disease could enter the body through the eyes! Cheltine Foods advertised eating their invalid biscuits might help avoid ‘flu.

The first record of an influenza death in Cheltenham is probably that of a volunteer nurse from New Court Hospital, which was on the Lansdown Road, a few yards from her home in Lypiatt Terrace. “Lena” Shaw died in March 1917 and she was given a military funeral with full honours at Cheltenham cemetery. (See separate article on Lena Shaw) The funeral party was headed by a firing party and two buglers of the Army Service Corps and a Guard of Honour of 50 wounded soldiers from New Court Hospital. A hint that the ‘flu was taking hold in Cheltenham could be gleaned from this notice in the Gloucestershire Echo in October 1918:

“We are receiving many complaints of the non-delivery of the Echo. The prevailing epidemic of influenza has laid a score of our boys aside and it has been impossible to replace them.”

The following day, the newspaper reported that one of the German Prisoners of War Stanislaw Bendzmerowski, who was billeted in Charlton House, Charlton Kings (now Spirax-Sarco on the Cirencester Road) had died from pneumonia following influenza. In June 1918, 42 German POWs arrived in Cheltenham to work as labourers at Toddington Orchard Farms. In the same newspaper, it was reported that Sir Hubert Parry, the composer, had died of influenza. His family were from Highnam Court, Gloucester and Sir Hubert wrote the famous anthem “Jerusalem”. Week beginning 12th October there had been 25 deaths from ‘flu in Cheltenham and the following week this had risen to 44 deaths. The Cheltenham Medical Officer of Health, Dr. Garrett, explained that death rates in the town were the highest since the scarlet fever outbreak in Cheltenham in 1876 and the Echo called the death rate “somewhat alarming”. The official death toll in England for the last three months of 1918 was 98,998.

The centre of the Spanish flu pandemic in Europe has been identified as Etaples in France. The town was the principal depot and transit camp for British troops in France and the point from which wounded men were taken to and ferried out from to hospitals in England, such as the eight VAD hospitals in Cheltenham. Etaples was home to a major convalescent area and 16 military hospitals as well as a depot with up to 80,000 troops being accommodated at any one time.

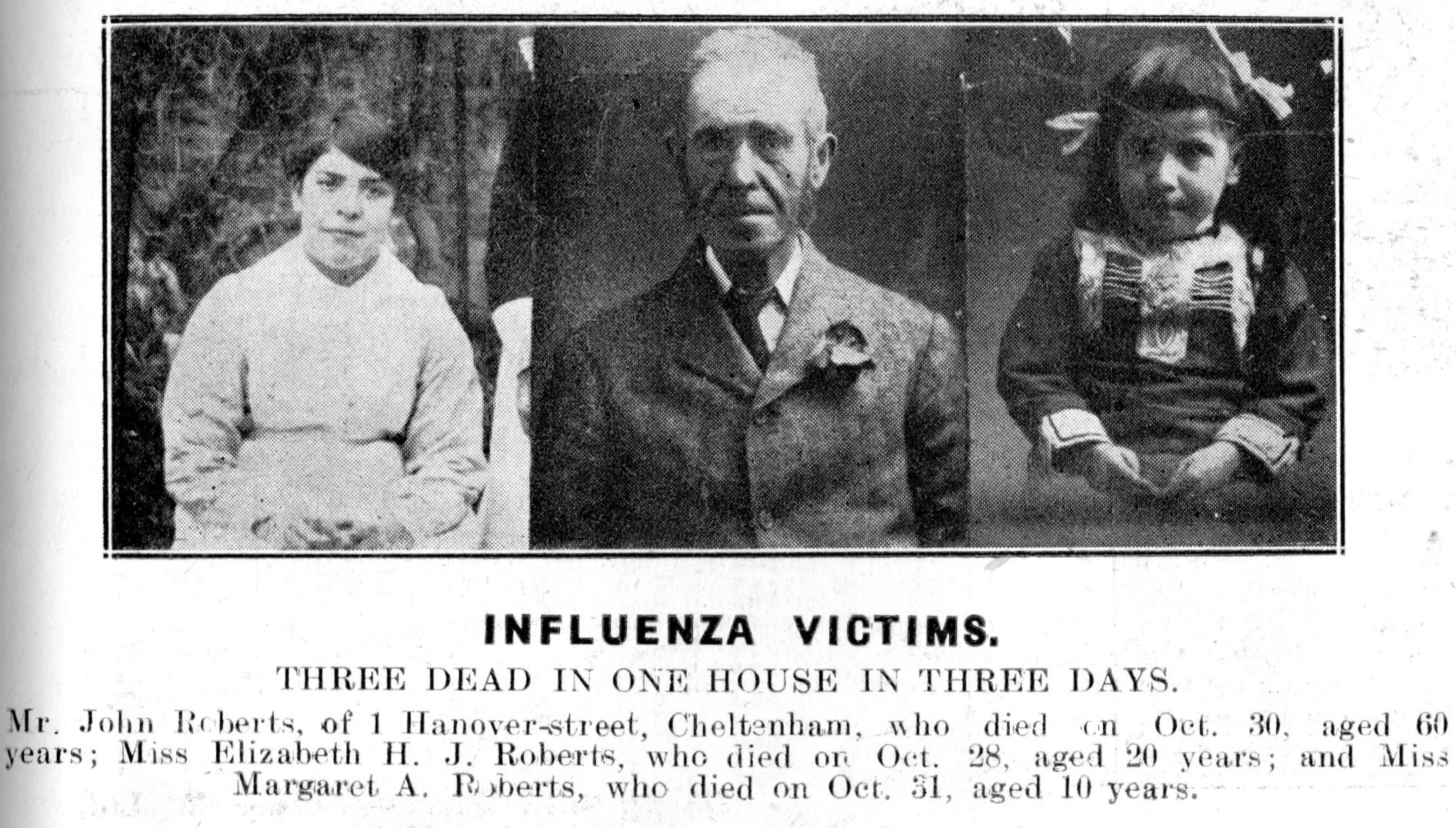

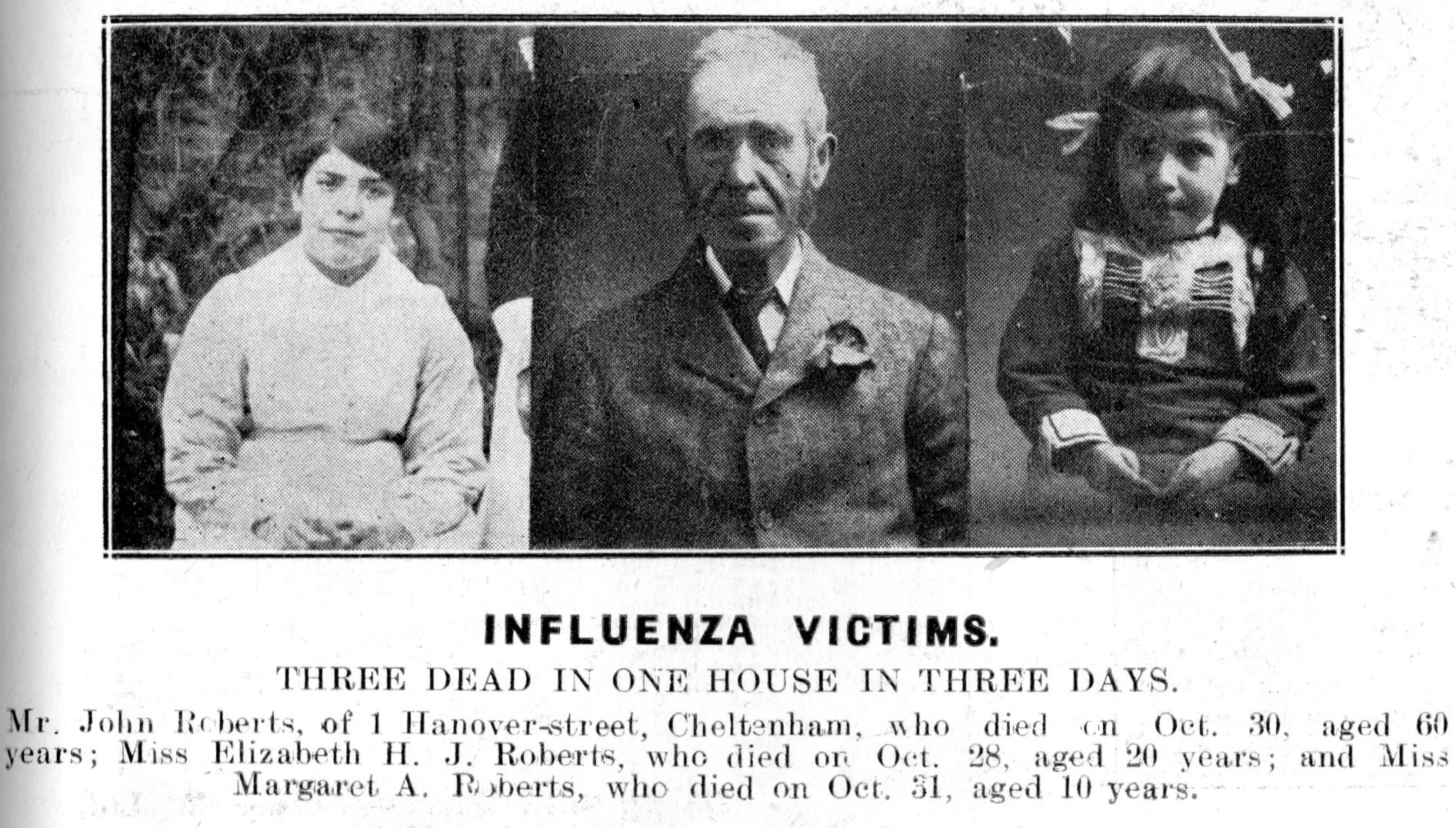

Cheltenham was a town with a steady influx of soldiers from the battlefields in Europe to the eight VAD hospitals in the town and also many troops were billeted in the large old houses. In August 1918, the town’s last military billeting consisted of 600 cadets of the newly formed Royal Air Force, followed a month later by members of the Women’s Royal Air Force, who were billeted in the YWCA. Under the Defence of the Realm Act the RAF had requisitioned The Town Hall, a local riding school and 33 private houses. Twenty year old Elizabeth Roberts of 1 Hanover Street had only been working as a WRAF Clerk for a few weeks, when she died of the ‘flu in October 1918. Her father had died two days earlier and her 10 year old sister, Margaret, died the day after Elizabeth. In 2018, as part of the Cheltenham Remembers project, Elizabeth was honoured when her name was added to the war memorial in the Promenade – the only woman from Cheltenham to be so commemorated.

In the book “Leaving All That Was Dear”, which contains details of those soldiers from Cheltenham who died in the Great War, Joe Devereux and Graham Sacker record the following soldiers whose deaths were recorded as being from influenza. It is interesting to note the wide geographical spread of the deaths and how all of them were under the age of 40. However, the authors identified 48 Cheltenham soldiers whose deaths were recorded as caused by pneumonia. Many ‘flu victims died of pneumonia as a secondary infection of the ‘flu.

In the coming months after the Armistice was signed in November 1918, many returning soldiers brought back the disease to the towns of England.

1917

March 2nd at 17 Lypiatt Terrace, Cheltenham died at home. Shaw, Anna Madeline (“Lena”) – Red Cross VAD Nurse at New Court Hospital, Cheltenham. 33 years old. Cheltenham

1918

October 21st Peshawar, India. Burrows, Arthur Henry – Driver Army Service Corps – died at Station Hospital, Peshawar. 24 years old. Fairview Road, Cheltenham

October 25th Fillievres, France. Du Boulay, Arthur – Colonel D.S.O. 38 years old. Bayshill, Cheltenham

October 28th Roberts, Elizabeth – WRAF Clerk – died at Cheltenham 20 years old Hanover Street

November 9th Pas de Calais, France Dennett, Frank – Corporal Army Service Corps – died at the 23rd Casualty Clearing Station at Brebières, Northern France 32 years old St. Phillip’s Terrace, Cheltenham

November 17th Aden, The Yemen. Beak, Douglas Eliot – Lance Corporal – died in British General Hospital, Aden 27 years old Keynsham Road, Cheltenham

November 17th Mesopotamia, Middle East Williams, Harry – Gunner -died Mesopotamia Age Unknown Swindon Place, Cheltenham

November 19th Rouen, France Ferguson, John Charles – Captain – died in No. 8 General Hospital Rouen 30 years old Bath Road, Cheltenham

November 21st Ely Cambridgeshire Heading, William Henry – Reverend Army Chaplain – died in Cambridgeshire 28 years old Brookway Road, Charlton Kings

December 23rd Marseilles, France Hawker, Albert Victor – Lieutenant – died in 81st General Hospital, Marseilles on his way home 26 years old St George’s Square, Cheltenham

24th December Hamburg, Germany Pulham, Arthur William – Private – after being released as a Prisoner of War for for years in Germany 24 years old Horsefair Street, Charlton Kings

Article by Neela Mann August 2020

Leave a Reply