Read this fascinating article about the contribution of local Cheltonian women during the First World War. Reproduced with kind permission of by Neela Mann (author of Cheltenham in the Great War) and the History Press.

Read this fascinating article about the contribution of local Cheltonian women during the First World War. Reproduced with kind permission of by Neela Mann (author of Cheltenham in the Great War) and the History Press.

How the well-organised women of Cheltenham contributed to the war effort

In the early years of the twentieth century there were large numbers of ex-colonial, retired military personnel in Cheltenham – a leisured class with time on their hands and a culture of looking after their ‘troops’. As the young men left for war, groups of women came forward to raise money, pack parcels, knit and sew for the soldiers, look after the influx of the wounded and volunteer for whatever task was needed.

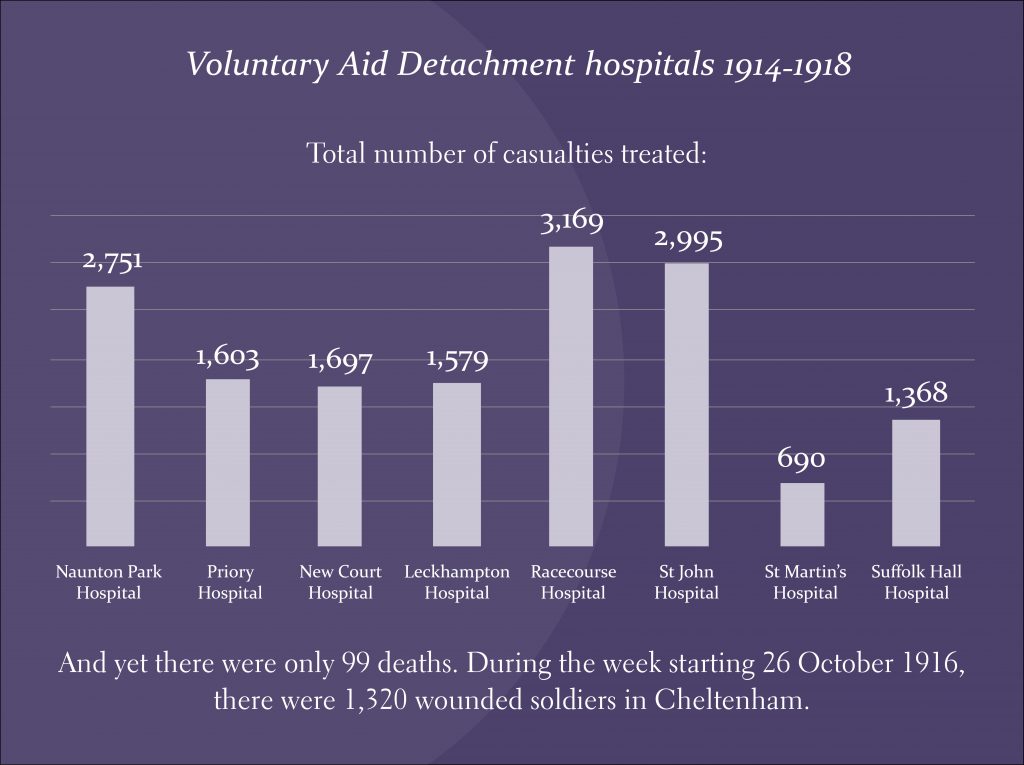

Hospitals

Cheltenham was a town with plenty of large houses and a number of schools of a size suitable for conversion to use as hospitals, and there were ample numbers of willing, able and available volunteers, many of whom were women. The town’s geographical location – on the train route from Southampton – made Cheltenham the ideal location for transportation from the front to the eight war hospitals eventually sited in the town. It is said by a local doctor that they took in ‘…warriors straight from the battlefields, the first field dressings still round their limbs.’

Cheltenham Ladies’ College, past and present pupils and staff ran and funded St. Martin’s Hospital. From June 1915, wounded soldiers came directly from the Front to Cheltenham by train arriving ‘…mud-caked and blood-stained.’

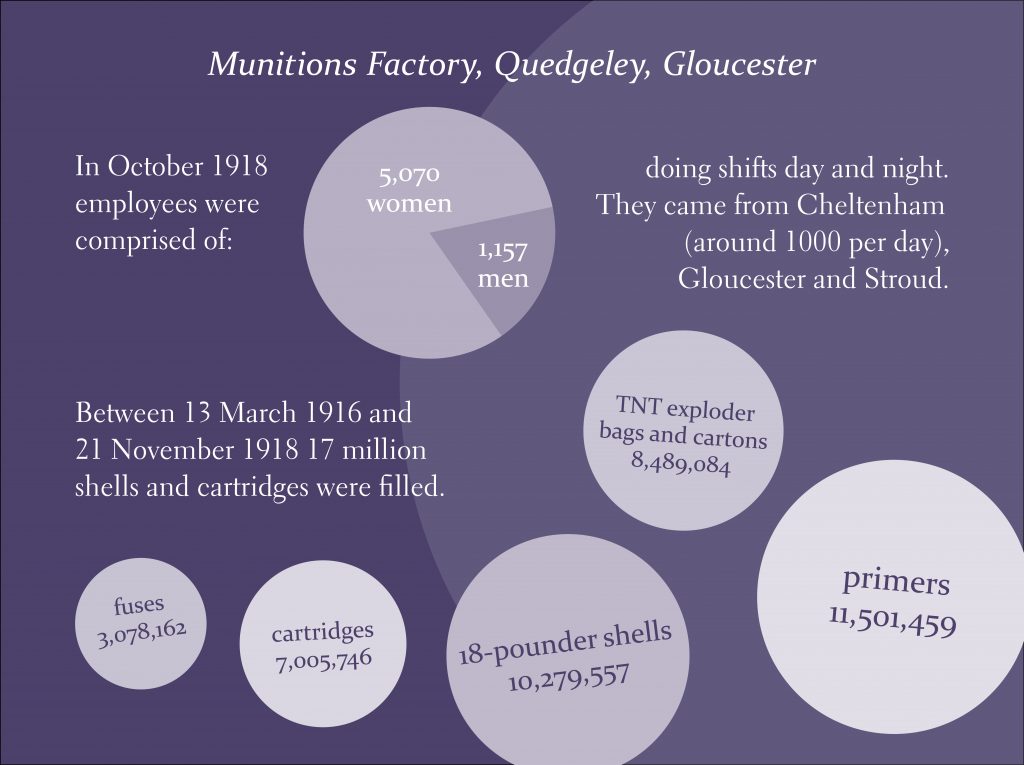

Munitions

As the war progressed, women were also able to help by taking up essential factory work. The munitions factory at Quedgeley (National (Shell) Filling Factory No. 5) started production in March 1916 responding to the shell crisis of May 1915. At its height the Gloucester factory had 6,364 workers, mainly women, of which 1000 came from Cheltenham every day on the train.

Munitions’ workers were known as ‘Tommy’s sisters’ or ‘Munitionettes’. Those whose skin turned yellow from working with TNT dust were nicknamed ‘Canaries’.

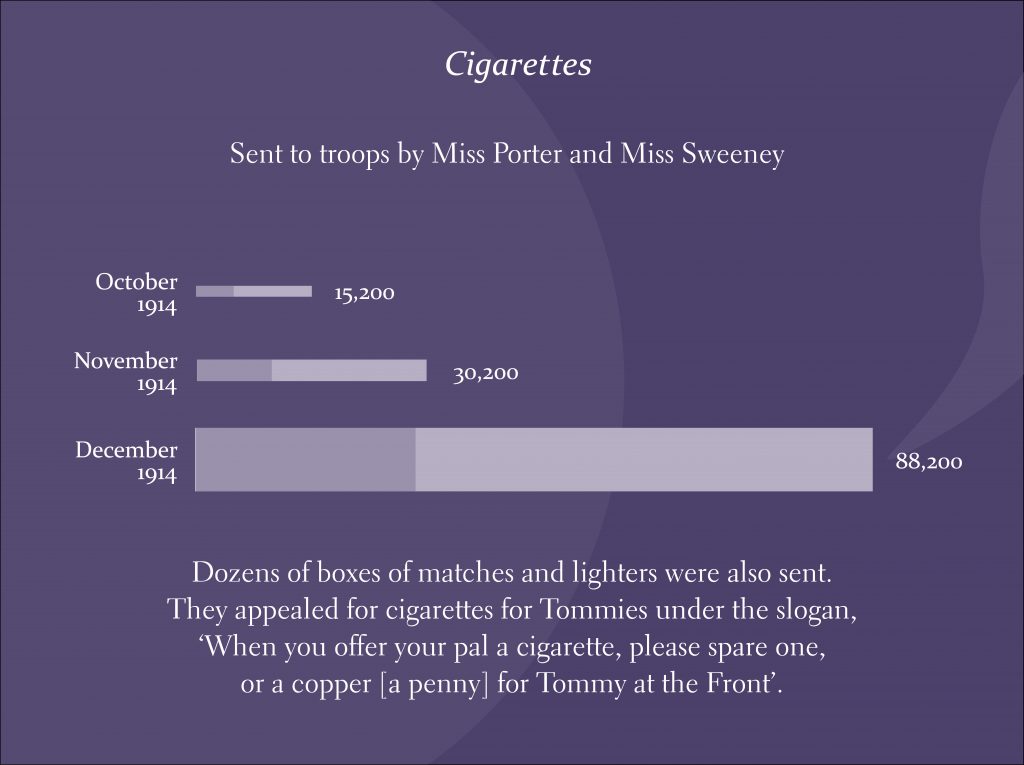

Cigarettes for Tommies

This was just one of many appeals. Cigarettes were considered necessary to boost soldiers’ morale. It was said ‘…with a cigarette between their lips, they can face discomforts cheerfully.’

There were plenty of roles for those who wanted to do something useful without necessarily getting their hands dirty. For instance, The County Cobblers were ‘voluntary ladies and gentlemen banded together’. They paid for the materials themselves and on average were making 136 slippers a week. Demand increased and in 1917 they made 3,800 pairs and were appealing for cuttings from linings, old hunting coats and riding habits, faded felt surrounds and cork lino. Their pattern for slippers had been adopted by the Red Cross nationally and the Cheltenham branch sent out slippers to far-away places like Salonica as well as France.

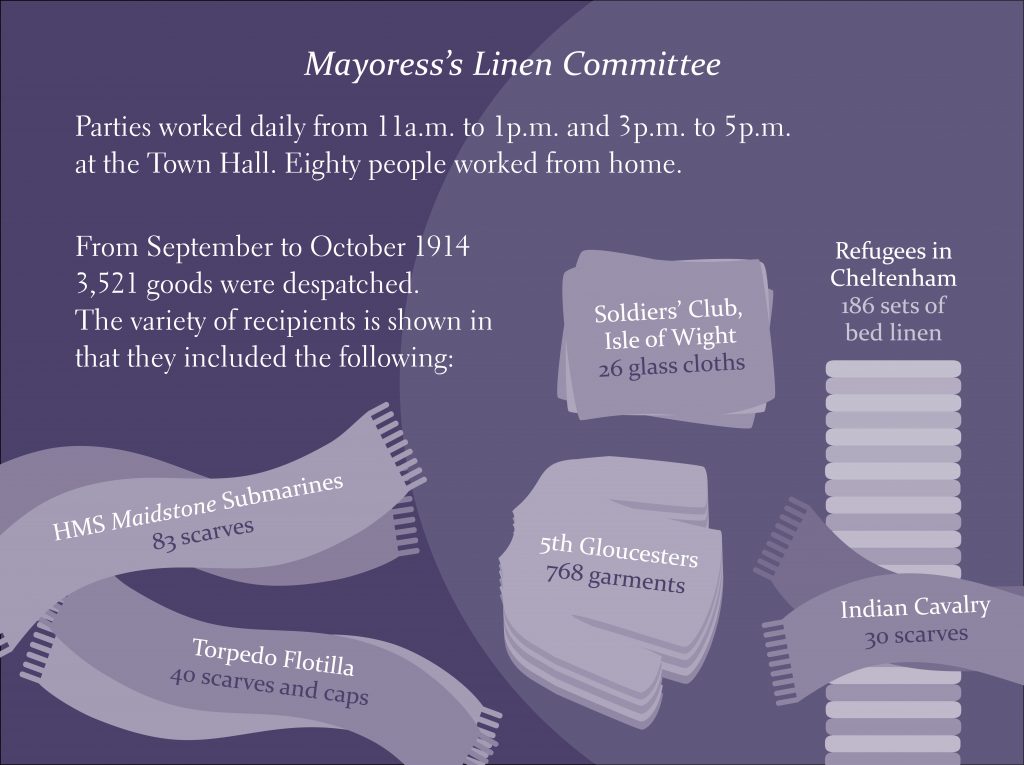

Linen goods

Other women used their domestic skills to provide knitted garments for soldiers and sailors. Mrs Richard Longland of Tate’s Hotel on the promenade organised a team of knitters who in just four weeks were able to supply every officer and man aboard HMS Gloucester with a scarf.

In Cheltenham in 1916, the Women’s Volunteer Reserve, made up of mainly suffragettes/suffragists had opened a soldiers’ club in addition to work as messengers for the Red Cross hospitals, taking wounded soldiers to the Picture Palace and giving them tea.

Cheltenham Ladies’ College pupils and staff contributed in many ways, including – making anaesthetics in the laboratories, clerking for the council as so many male clerks had gone to war, picking herbs for medicines and working on farms collecting the harvest during their holidays. St. Martin’s Hospital was run and funded by past and present pupils and teachers who had been trained at the college in first aid since 1909. The college organised a system to collect and sort waste from the boarding houses. When a ton of paper was collected it was despatched to Avonmouth for munition making. Bones were sorted and sent to make glycerine for munitions and biscuit tins and bottles packed back to their original firms. Empty tins were collected in the yard and allowed to get rusty and, when a ton had been collected (they didn’t quite collect enough), it was to be steam-rollered flat and sent to France for road building. Even soot from college chimneys and honey from bees, which had taken up residence in a college house, was collected.

By Neela Mann – author of Cheltenham in the Great War published by the History Press.

Leave a Reply