Extracts from Cheltenham in the Great War by Neela Mann (2016, The History Press)

“Cheltenham’s Prisoners of War and two remarkable ladies

The large basement at Dumfries House, in Bayshill (now County House) became the source of a life line to 197 Prisoners of War (POWs) from Cheltenham. The house was the home of Mrs Elphinstone Shaw, wife of an Indian Army Colonel and daughter and sister in law of Indian Army Generals. Having been married in India, Mrs Shaw returned to Cheltenham in 1895 to join her sister and family.

Since October 1914 Mrs Shaw had been sending parcels of her own accord to prisoners of war from Cheltenham. The Prisoners of War Fund Committee, part of Cheltenham Trader’s association, was formed in July 1915, as a result of “Soldier’s Day” held in the town in June. Mrs Shaw and her daughter Mrs Hearle Cole were asked to serve on the committee and to take on, officially, the organisation and despatch of parcels to captured Cheltenham soldiers. At the time it was considered that “their onerous duties will extend over some weeks, maybe months”!

The first batch of thirteen parcels, sent out in July 1915, contained sugar, Nestle milk, café au lait, golden syrup, herrings, bacon, camp pies, towels and soap, pencils, tobacco, bread, cake, and pipes. Local traders had to submit a tender to supply the organisation.

A letter appeared in the Gloucestershire Echo from Mrs Hearle Cole on 17th July 1915, advising people to be aware the German authorities had requested that if they were to send their own parcels to POWs, the parcels must be sewn up in canvas, linen or sacking with the address to be written on linen and sewn on to the parcel, as brown paper parcels were falling apart.

Letters of thanks came flowing in to Dumfries House from POWs and their families and as a result, in September 1915, Mrs Shaw was asking for warm vests and worn boots for the POWs, as they had requested. Three months later the Echo had started a fund to supplement money coming from the Trader’s Association efforts, so great was the need, and this fund continued throughout the war.

Some townspeople ‘adopted’ a POW and gave money regularly to pay for his parcels. By December 1915 Mrs Shaw and her team of volunteers were sending 80 parcels a month at a cost of 5s., each weighing 11lbs and including a cardigan jacket, muffler, cake, sweets, roast beef, raisins, tobacco and cigarettes, apple mould, milk, tea, cocoa, Vaseline and a handkerchief.

Mrs Shaw was able to pass on, through the pages of the newspapers, useful snippets of advice to POWs’ families. One returning soldier wrote “I shall always remember Mrs Shaw who gave me food when I was hungry and consoled me when I was sad.”

By September 1917, demand had risen to 70 parcels per week, packed by several lady assistants and the Echo fund had raised £1,166 15s 7d. The work, by this time, was considered to be of sufficient importance to be taken under government ‘control’ but was still not given any government subsidies or grants. In effect, Cheltenham POWs were supported by their own people. When food rationing was brought in, the ‘government control’ was evident in that the only food allowed out of the country was to be specifically for POWs but not for internees. 9th December 1917 Mrs Shaw died suddenly. She was held in such high regard that her obituary spoke of her thus: “She was a grand, old lady, one of those staunch, sterling fine characters who sticks to a job however arduous.” Mrs Shaw was typical of Cheltenham’s Anglo-Indian ex-military ladies, used to rallying support to look after ‘the troops’. As one would expect, her daughter, Mrs Hearle Cole, took on the running of the organisation, with help from her own daughter, Mrs Austin Miller.

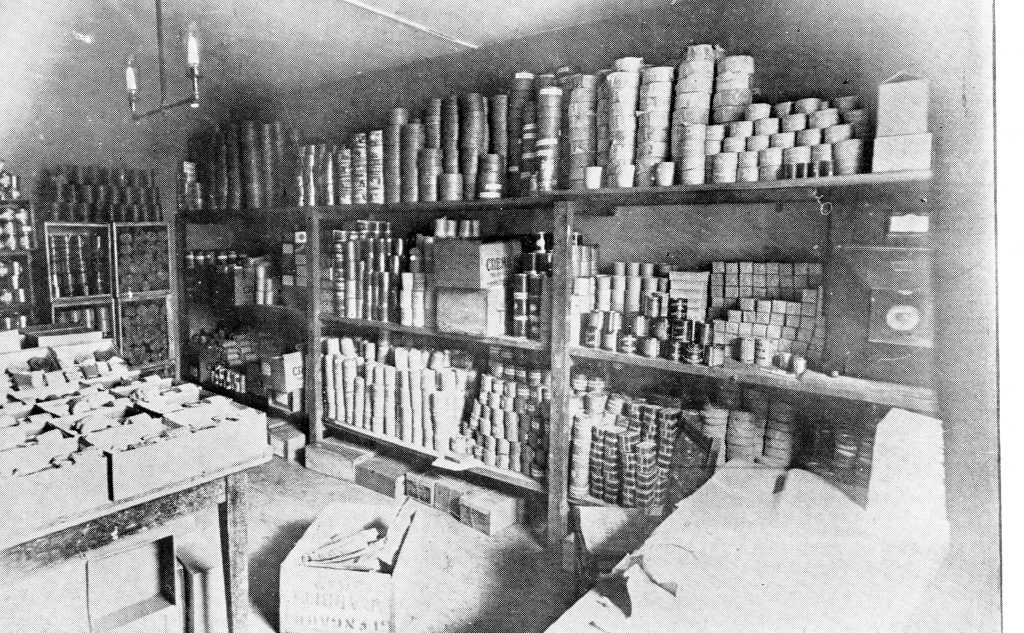

Eventually, ten lady volunteers, the domestic staff of Dumfries House plus the gardener, Mr Matty, were sending out an average of 1,020 parcels monthly, weighing 10lb. There were ‘bonded’ goods – tea, coffee, sugar, syrup, chocolate, tobacco and cigarettes, stores of which had to be checked weekly by Customs and Excise officers. Mrs Hearle Cole was answerable to the Central POW Committee in London and to 42 regimental care committees.

Letters from the men’s relatives and hundreds of cards from the men had to be answered regularly and personally by Mrs Elphinstone Shaw and by the end of the war Mrs Hearle Cole had to take on a secretary to cope with the volume. One letter of thanks, written on behalf of the Cheltenham POWs in a German camp, told the ladies that their work was vital to the men but that sometimes parcels needed better wrapping, such as the one received where the soap had become mixed with the jam! Another from a Bishop’s Cleeve man told of having been moved around POW camps and eventually receiving 36 parcels at once.

The financial situation in May 1918 was precarious; there was only enough money for one month’s parcels – the cost of parcels had almost doubled to 8s each. In a newspaper appeal it was reported that “Due to recent great drives by the Germans hundreds of prisoners were taken including some from Cheltenham…so it is only fair to warn that the demands of funds are now exceedingly heavy…and operations may have to be suspended.” In response, another, even larger “Prisoner’s Day” was held on August Bank Holiday Monday, with a total of 47 stalls and a procession of 64 entrants in fancy dress, organised and controlled by Mrs Ringer. The event raised a staggering £3,300 from the people of Cheltenham.

Cheltenham POWs who presented themselves at Dumfries House when freed, received 15lb of food, a shirt, muffler and socks from Miss Wethered’s County Voluntary Association, £2 on arrival and £1 per week for eight weeks from funds. At the POW Thanksgiving Dinner in December 1918, Mrs Hearle Cole received …a tornado of applause such as she is unlikely to forget” and a rose bowl engraved with the Borough Arms of Cheltenham and an inscription with the names of 197 men who were POWs. The four maids were presented with gold brooches and the gardener, Mr Matty, with a case of pipes. Five days later 80 of the men made a pilgrimage to Cheltenham Cemetery and placed a wreath, crown and cross on Mrs Elphinstone Shaw’s grave.

Leave a Reply